In May of this year, NOBELIUM (the Russian government threat actor behind SolarWinds attacks) leveraged the legitimate mass-mailing service Constant Contact to masquerade as a U.S.-based development organization and distribute malicious URLs to a wide variety of organizations and industry verticals.

Between July 13 and July 16, 2021, INKY detected 121 phishing emails in a similar attack that originated from a compromised Mailgun email marketing account used by a large Food & Beverage Company. Mailgun is a similar email marketing service to Constant Contact and is widely recognized in the industry based on the email volumes it distributes.

Of those 121 attacks, two were fake voicemail notifications with malware attachments (also known as vishing), 14 impersonated USAA Bank and had mail.company[.]com links that redirected to a malicious USAA Bank credential harvesting site, and the other 105 impersonated Microsoft and had mail.company[.]com links that redirected to a malicious Microsoft credential harvesting site.

The attacks described here seem to mimic the NOBELIUM techniques—using a compromised third-party email marketing platform to launch phishing and credential harvesting attacks. INKY has no evidence to suggest the same actors are involved in these attacks, it appears to be a case of copying a successful attack vector used by NOBELIUM. INKY continues to investigate these attacks.

Quick Takes: Attack Flow Overview

- Type: phishing

- Vector: Large Food & Beverage Company’s hijacked email marketing account

- Payload: credential harvesting and malware

- Techniques: phishing email that uses mail.company[.]com as redirector to malicious sites

- Platform: Office365

- Target: Microsoft and USAA users, others

The Attack

All the phishing attempts leveraged the same service: a compromised Mailgun account that the company used for mass email marketing. However, they differed in the details.

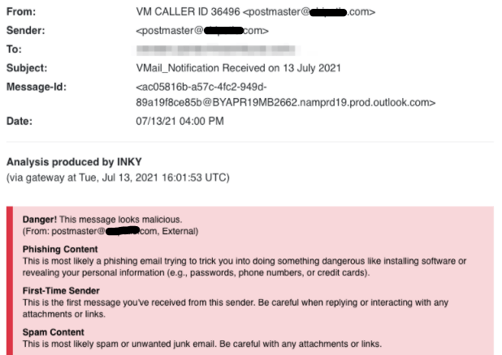

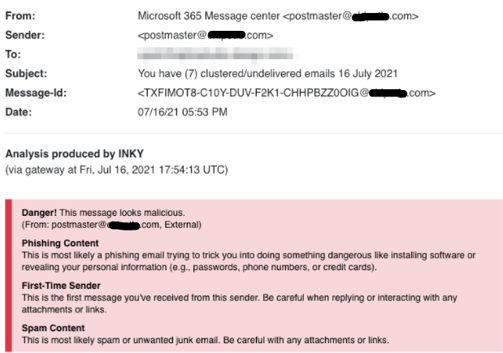

Of the 121 phishing emails detected by INKY (after they slipped past the secure email gateway), two were vishing attacks, fake voicemail notifications with malware attachments. Below is one of the emails that an INKY user received. Here, we show only the visible header and, just below that, the INKY banner with its analysis.

Fake Voicemail

There was no voicemail message, only an attachment that, when clicked upon, delivered malware to the recipient’s device. Four of INKY’s detection modules fired during analysis, and overall danger assessment, one that noted that phishing content was likely, a first-time-sender alert, and, for good measure, a spam assessment.

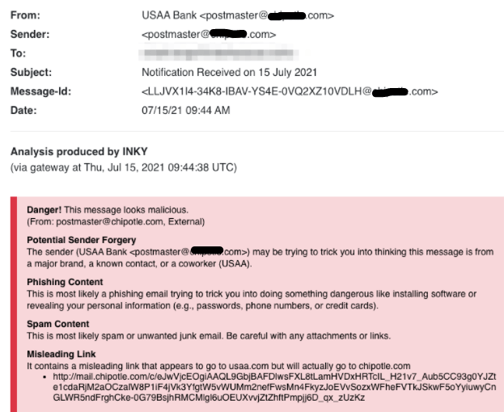

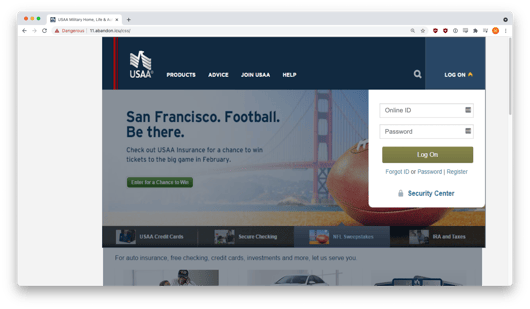

USAA Spoof

More prevalent, 14 phishing attempts tried to impersonate USAA, a diversified financial services company with retail banking business. The scam emails contained mail.company[.]com links that redirected to a malicious USAA Bank credential-harvesting site. The sample below shows how INKY detected brand forgery, phishing content, and a misleading link. Instead of leading to a USAA website, the link took the unwary clicker to a credential-harvesting site by way of a Company site. While you might bank on having a burrito for lunch, in no way is this company an actual bank.

Here’s what the credential-harvesting site looked like:

It presented a pretty good imitation of an actual USAA login page, replete with a perfect copy of the USAA logo (down to the trademark symbol), local details, and a nice dialogue box where you could enter your ID and password. The black hats can make these pages by simply cloning the real page, changing just one or two details to the underlying HTML, and voila! A credential-harvesting page is born.

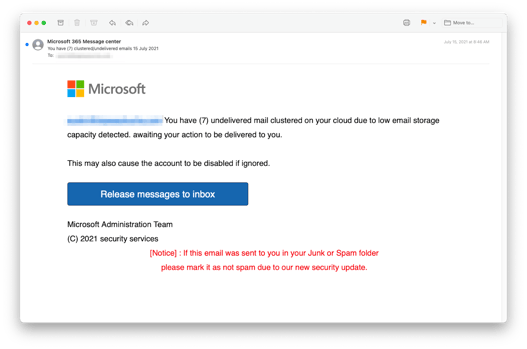

Yet Another Microsoft Hack

As is often the case in the phishing world, by far the bulk of these Company attacks tried to impersonate Microsoft. The giant software company is often the subject of impersonations because Microsoft credentials are highly valuable. Almost everyone has a Microsoft account, and logins there can lead to all kinds of interesting data, including other logins, trade secrets, financial details, and other intelligence. Thus, it is not surprising that INKY identified 105 phishing emails during that three-day stretch all of which had mail.company[.]com links that redirected the recipient to a malicious Microsoft credential-harvesting site. Below are the message header details and the INKY banner showing the results of its analysis.

Here is a screenshot of the fake Microsoft email:

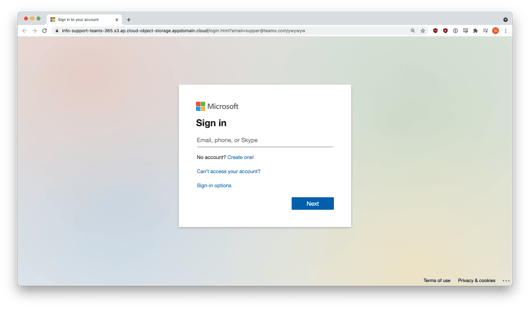

And here is a view of the fake Microsoft login on the credential-harvesting site:

Techniques

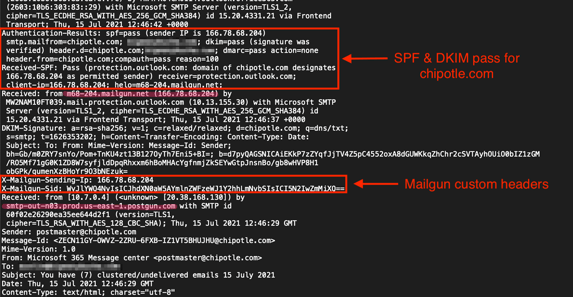

This attack was highly effective because all phishing emails came from an authentic Mailgun IP address (166.78.68.204), passed email authentication (SPF and DKIM) for company[.]com, and used high reputation mail.company[.]com URLs as redirectors to malicious sites.

Analysis of the email headers revealed that the messages originated from Mailgun servers (postgun.com and mailgun.net) and passed email authentication for company[.]com.

A view of a sample header, below, shows how the Microsoft impersonation phishing emails came through Company's domain and made use of Mailgun’s custom headers. An examination of Company's Domain Name Service (DNS) records also turned up the Company-Mailgun relationship.

Recap of Techniques:

- Brand impersonation — uses elements of a well-known brand to make an email look as if it came from that company

- Malware attachment — looks like a benign attachment but when clicked initiates a malware injection into the recipient’s devices

- URL redirect — makes a link appear to lead to a trusted site when it actually passes the unwary clicker onto a booby-trapped webpage

- Credential harvesting — occurs when a victim thinks they are logging in to one of their resource sites but is actually entering credentials into a dialogue box owned by attackers

- Compromised email accounts — are used by phishers because they can pass most security software tests, allowing phishing emails to slip past corporate defenses and into hapless recipients’ inboxes

Best Practices: Guidance and Recommendations

It is important that recipients (and email security software) notice the discrepancy between a sender’s display name (Microsoft, USAA, VM Caller ID) and its actual email address (postmaster@company[.]com). It’s pretty clear that Microsoft and USAA would never use mail.company[.]com URLs to resolve account issues. But secure email gateways often check only whether the sending domain is legitimate and is transmitting from an approved range of IP addresses. That schema can lead to absurdities like Microsoft apparently sending an account notice via Company. One recommendation is to use an advanced anti-phishing solution that compares the apparent sender with the underlying sending domain. If the apparent sender doesn’t actually control that domain, a proven anti-phishing solution will notify the user. Of course, always be skeptical of sites asking for credentials of any kind. If you do enter credentials for a site regularly, be sure to check the originating email address and look for discrepancies from your normal sign-in process.

It’s also a good idea to watch out for unusual email attachments. For example, real voicemail notifications always use audio attachments like .mp3 and .wav.

Look for the next edition of INKY’s Fresh Phish blog coming soon.

Fresh Phish examples discovered and analyzed initially by Bukar Alibe, Data Analyst, INKY

About INKY

Headquartered in College Park, Maryland, INKY leads the industry in mail protection powered by unique computer vision, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. The company’s flagship product, INKY Phish Fence, uses these novel techniques to “see” each email much like a human does, to block phishing attacks that get through every other system. INKY founder Dave Baggett also co-founded ITA Software, the industry-leading airfare search company purchased by Google in 2011 for $730M, which now powers Google Flights®. For more information, please visit https://INKY.com/.